- Home

- Audrey Niffenegger

The Time Traveler's Wife Page 10

The Time Traveler's Wife Read online

Page 10

"Tie him to the tree." I hand her the gun, jerk Jason's hands into position behind the tree, and duct tape them together. There's almost a full roll of duct tape, and I intend to use all of it. Jason is breathing strenuously, wheezing. I step around him and look at Clare. She looks at Jason as though he is a bad piece of conceptual art. "Are you asthmatic?"

He nods. His pupils are contracted into tiny points of black. "I'll get his inhaler," says Clare. She hands the gun back to me and ambles off through the woods along the path we came down. Jason is trying to breathe slowly and carefully. He is trying to talk.

"Who...are you?" he asks, hoarsely.

"I'm Clare's boyfriend. I'm here to teach you manners, since you have none." I drop my mocking tone, and walk close to him, and say softly, "How could you do that to her? She's so young. She doesn't know anything, and now you've completely fucked up everything..."

"She's a...cock...tease."

"She has no idea. It's like torturing a kitten because it bit you."

Jason doesn't answer. His breath comes in long, shivering whinnies. Just as I am becoming concerned, Clare arrives. She holds up the inhaler, looks at me. "Darling, do you know how to use this thing?"

"I think you shake it and then put it in his mouth and press down on the top." She does this, asks him if he wants more. He nods. After four inhalations, we stand and watch him gradually subside into more normal breathing.

"Ready?" I ask Clare.

She holds up the scissors, makes a few cuts in the air. Jason flinches. Clare walks over to him, kneels, and begins to cut off his clothes. "Hey," says Jason.

"Please be quiet," I say. "No one is hurting you. At the moment." Clare finishes cutting off his jeans and starts on his T-shirt. I start to duct tape him to the tree. I begin at his ankles, and wind very neatly up his calves and thighs. "Stop there," Clare says, indicating a point just below Jason's crotch. She snips off his underwear. I start to tape his waist. His skin is clammy and he's very tan everywhere except inside a crisp outline of a Speedo-type bathing suit. He's sweating heavily. I wind all the way up to his shoulders, and stop, because I want him to be able to breathe. We step back and admire our work. Jason is now a duct-tape mummy with a large erection. Clare begins to laugh. Her laugh sounds spooky, echoing through the woods. I look at her sharply. There's something knowing and cruel in Clare's laugh, and it seems to me that this moment is the demarcation, a sort of no-man's-land between Clare's childhood and her life as a woman.

"What next?" I inquire. Part of me wants to turn him into hamburger and part of me doesn't want to beat up somebody who's taped to a tree. Jason is bright red. It contrasts nicely with the gray duct tape.

"Oh," says Clare. "You know, I think that's enough."

I am relieved. So of course I say, "You sure? I mean there are all sorts of things I could do. Break his eardrums? Nose? Oh, wait, he's already broken it once himself. We could cut his Achilles' tendons. He wouldn't be playing football in the near future."

"No!" Jason strains against the tape.

"Apologize, then," I tell him.

Jason hesitates. "Sorry."

"That's pretty pathetic--"

"I know," Clare says. She fishes around in her purse and finds a Magic Marker. She walks up to Jason as though he is a dangerous zoo animal, and begins to write on his duct-taped chest. When she's done, she stands back and caps her marker. She's written an account of their date. She sticks the marker back in her purse and says, "Let's go."

"You know, we can't just leave him. He might have another asthma attack."

"Hmm. Okay, I know. I'll call some people."

"Wait a minute," says Jason.

"What?" says Clare.

"Who are you calling? Call Rob."

Clare laughs. "Uh-uh. I'm going to call every girl I know."

I walk over to Jason and place the muzzle of the gun under his chin. "If you mention my existence to one human and I find out about it I will come back and I will devastate you. You won't be able to walk, talk, eat, or fuck when I'm done. As far as you know, Clare is a nice girl who for some inexplicable reason doesn't date. Right?"

Jason looks at me with hatred. "Right."

"We've dealt with you very leniently, here. If you hassle Clare again in any way you will be sorry."

"Okay."

"Good." I place the gun back in my pocket. "It's been fun."

"Listen, dickface--"

Oh, what the hell. I step back and put my whole weight into a side kick to the groin. Jason screams. I turn and look at Clare, who is white under her makeup. Tears are running down Jason's face. I wonder if he's going to pass out. "Let's go," I say. Clare nods. We walk back to the car, subdued. I can hear Jason yelling at us. We climb in, Clare starts the car, turns, and rockets down the driveway and onto the street.

I watch her drive. It's beginning to rain. There's a satisfied smile playing around the edges of her mouth. "Is that what you wanted?" I ask.

"Yes," says Clare. "That was perfect. Thank you."

"My pleasure." I'm getting dizzy. "I think I'm almost gone."

Clare pulls onto a sidestreet. The rain is drumming on the car. It's like riding through a car wash. "Kiss me," she demands. I do, and then I'm gone.

Monday, September 28, 1987 (Clare is 16)

CLARE: At school on Monday, everybody looks at me but no one will speak to me. I feel like Harriet the Spy after her classmates found her spy notebook. Walking down the hall is like parting the Red Sea. When I walk into English, first period, everyone stops talking. I sit down next to Ruth. She smiles and looks worried. I don't say anything either but then I feel her hand on mine under the table, hot and small. Ruth holds my hand for a moment and then Mr. Partaki walks in and she takes her hand away and Mr. Partaki notices that everyone is uncharacteristically silent. He says mildly, "Did you all have a nice weekend?" and Sue Wong says, "Oh, yes" and there's a shimmer of nervous laughter around the room. Partaki is puzzled, and there's an awful pause. Then he says, "Well, great, then let s embark on Billy Budd. In 1851, Herman Melville published Moby-Dick, or, The Whale, which was greeted with resounding indifference by the American public..." It's all lost on me. Even with a cotton undershirt on, my sweater feels abrasive, and my ribs hurt. My classmates arduously fumble their way through a discussion of Billy Budd. Finally the bell rings, and they escape. I follow, slowly, and Ruth walks with me.

"Are you okay?" she asks.

"Mostly."

"I did what you said."

"What time?"

"Around six. I was afraid his parents would come home and find him. It was hard to cut him out. The tape ripped off all his chest hair."

"Good. Did a lot of people see him?"

"Yeah, everybody. Well, all the girls. No guys, as far as I know." The halls are almost empty. I'm standing in front of my French classroom. "Clare, I understand why you did it, but what I don't get is how you did it."

"I had some help."

The passing bell rings and Ruth jumps. "Oh my god. I've been late to gym five times in a row!" She moves away as though repelled by a strong magnetic field. "Tell me at lunch," Ruth calls as I turn and walk into Madame Simone's room.

"Ah, Mademoiselle Abshire, asseyez-vous, s'il vous plait." I sit between Laura and Helen. Helen writes me a note: Good for you. The class is translating Montaigne. We work quietly, and Madame walks around the room, correcting. I'm having trouble concentrating. The look on Henry's face after he kicked Jason: utterly indifferent, as though he had just shaken his hand, as though he was thinking about nothing in particular, and then he was worried because he didn't know how I would react, and I realized that Henry enjoyed hurting Jason, and is that the same as Jason enjoying hurting me? But Henry is good. Does that make it okay? Is it okay that I wanted him to do it?

"Clare, attendez," Madame says, at my elbow.

After the bell once again everyone bolts out. I walk with Helen. Laura hugs me apologetically and runs off to her music class at the other end of

the building. Helen and I both have third-period gym.

Helen laughs. "Well, dang, girl. I couldn't believe my eyes. How'd you get him taped to that tree?"

I can tell I'm going to get tired of that question. "I have a friend who does things like that. He helped me out."

"Who is 'he'?"

"A client of my dad's," I lie.

Helen shakes her head. "You're such a bad liar." I smile, and say nothing.

"It's Henry, right?"

I shake my head, and put my finger to my lips. We have arrived at the girls' gym. We walk into the locker room and abracadabra! all the girls stop talking. Then there's a low ripple of talk that fills the silence. Helen and I have our lockers in the same bay. I open mine and take out my gym suit and shoes. I have thought about what I am going to do. I take off my shoes and stockings, strip down to my undershirt and panties. I'm not wearing a bra because it hurt too much.

"Hey, Helen," I say. I peel off my shirt, and Helen turns.

"Jesus Christ, Clare!" The bruises look even worse than they did yesterday. Some of them are greenish. There are welts on my thighs from Jason's belt. "Oh, Clare." Helen walks to me, and puts her arms around me, carefully. The room is silent, and I look over Helen's shoulder and see that all the girls have gathered around us, and they are all looking. Helen straightens up, and looks back at them, and says, "Well?" and someone in the back starts to clap, and they are all clapping, and laughing, and talking, and cheering, and I feel light, light as air.

Wednesday, July 12, 1995 (Clare is 24, Henry is 32)

CLARE: I'm lying in bed, almost asleep, when I feel Henry's hand brushing over my stomach and realize he's back. I open my eyes and he bends down and kisses the little cigarette burn scar, and in the dim night light I touch his face. "Thank you," I say, and he says, "It was my pleasure," and that is the only time we ever speak of it.

Sunday, September 11, 1988 (Henry is 36, Clare is 17)

HENRY: Clare and I are in the Orchard on a warm September afternoon. Insects drone in the Meadow under golden sun. Everything is still, and as I look across the dry grasses the air shimmers with warmth. We are under an apple tree. Clare leans against its trunk with a pillow under her to cushion the tree roots. I am lying stretched out with my head in her lap. We have eaten, and the remains of our lunch lie scattered around us, with fallen apples interspersed. I am sleepy and content. It is January in my present, and Clare and I are struggling. This summer interlude is idyllic.

Clare says, "I'd like to draw you, just like that."

"Upside down and asleep?"

"Relaxed. You look so peaceful."

Why not? "Go ahead." We are out here in the first place because Clare is supposed to be drawing trees for her art class. She picks up her sketchbook and retrieves the charcoal. She balances the book on her knee. "Do you want me to move?" I ask her.

"No, that would change it too much. As you were, please." I resume staring idly at the patterns the branches make against the sky.

Stillness is a discipline. I can hold quite still for long stretches of time when I'm reading, but sitting for Clare is always surprisingly difficult. Even a pose that seems very comfortable at first becomes torture after fifteen minutes or so. Without moving anything but my eyes, I look at Clare. She is deep in her drawing. When Clare draws she looks as though the world has fallen away, leaving only her and the object of her scrutiny. This is why I love to be drawn by Clare: when she looks at me with that kind of attention, I feel that I am everything to her. It's the same look she gives me when we're making love. Just at this moment she looks into my eyes and smiles.

"I forgot to ask you: when are you coming from?"

"January, 2000."

Her face falls. "Really? I thought maybe a little later."

"Why? Do I look so old?"

Clare strokes my nose. Her fingers travel across the bridge and over my brows. "No, you don't. But you seem happy and calm, and usually when you come from 1998, or '99 or 2000, you're upset, or freaked out, and you won't tell me why. And then in 2001 you're okay again."

I laugh. "You sound like a fortune teller. I never realized you were tracking my moods so closely."

"What else have I got to go on?"

"Remember, it's stress that usually sends me in your direction, here. So you shouldn't get the idea that those years are unremittingly horrible. There are lots of nice things in those years, too."

Clare goes back to her drawing. She has given up asking me about our future. Instead she asks, "Henry, what are you afraid of?"

The question surprises me and I have to think about it. "Cold," I say. "I am afraid of winter. I am afraid of police. I am afraid of traveling to the wrong place and time and getting hit by a car or beat up. Or getting stranded in time, and not being able to come back. I am afraid of losing you."

Clare smiles. "How could you lose me? I'm not going anywhere."

"I worry that you will get tired of putting up with my undependableness and you will leave me."

Clare puts her sketchbook aside. I sit up. "I won't ever leave you," she says. "Even though you're always leaving me."

"But I never want to leave you."

Clare shows me the drawing. I've seen it before; it hangs next to Clare's drawing table in her studio at home. In the drawing I do look peaceful. Clare signs it and begins to write the date. "Don't," I say. "It's not dated."

"It's not?"

"I've seen it before. There's no date on it."

"Okay." Clare erases the date and writes Meadowlark on it instead. "Done." She looks at me, puzzled. "Do you ever find that you go back to your present and something has changed? I mean, what if I wrote the date on this drawing right now? What would happen?"

"I don't know. Try it," I say, curious. Clare erases the word Meadowlark and writes September 11, 1988.

"There," she says, "that was easy." We look at each other, bemused. Clare laughs. "If I've violated the spacetime continuum it isn't very obvious."

"I'll let you know if you've just caused World War III." I'm starting to feel shaky. "I think I'm going, Clare." She kisses me, and I'm gone.

Thursday, January 13, 2000 (Henry is 36, Clare is 28)

HENRY: After dinner I'm still thinking about Clare's drawing, so I walk out to her studio to look at it. Clare is making a huge sculpture out of tiny wisps of purple paper; it looks like a cross between a Muppet and a bird's nest. I walk around it carefully and stand in front of her table. The drawing is not there.

Clare comes in carrying an armful of abaca fiber. "Hey." She throws it on the floor and walks over to me. "What's up?"

"Where's that drawing that used to hang right there? The one of me?"

"Huh? Oh, I don't know. Maybe it fell down." Clare dives under the table and says, "I don't see it. Oh, wait here it is." She emerges holding the drawing between two fingers. "Ugh, it's all cobwebby." She brushes it off and hands it to me. I look it over. There's still no date on it.

"What happened to the date?"

"What date?"

"You wrote the date at the bottom, here. Under your name. It looks like it's been trimmed off."

Clare laughs. "Okay. I confess. I trimmed it."

"Why?"

"I got all freaked by your World War III comment. I started thinking, what if we never meet in the future because I insisted on testing this out?"

"I'm glad you did."

"Why?"

"I don't know. I just am." We stare at each other, and then Clare smiles, and I shrug, and that's that. But why does it seem as though something impossible almost happened? Why do I feel so relieved?

CHRISTMAS EVE, ONE

(ALWAYS CRASHING IN THE SAME CAR)

Saturday, December 24, 1988 (Henry is 40, Clare is 17)

HENRY: It's a dark winter afternoon. I'm in the basement in Meadowlark House in the Reading Room. Clare has left me some food: roast beef and cheese on whole wheat with mustard, an apple, a quart of milk, and an entire plastic tub of Christmas cookies, snowb

alls, cinnamon-nut diamonds, and peanut cookies with Hershey's Kisses stuck into them. I am wearing my favorite jeans and a Sex Pistols T-shirt. I ought to be a happy camper, but I'm not: Clare has also left me today's South Haven Daily; it's dated December 24, 1988. Christmas Eve. This evening, in the Get Me High Lounge, in Chicago, my twenty-five-year-old self will drink until I quietly slide off the bar stool and onto the floor and end up having my stomach pumped at Mercy Hospital. It's the nineteenth anniversary of my mother's death.

I sit quietly and think about my mom. It's funny how memory erodes. If all I had to work from were my childhood memories, my knowledge of my mother would be faded and soft, with a few sharp moments standing out. When I was five I heard her sing Lulu at the Lyric Opera. I remember Dad, sitting next to me, smiling up at Mom at the end of the first act with utter exhilaration. I remember sitting with Mom at Orchestra Hall, watching Dad play Beethoven under Boulez. I remember being allowed to come into the living room during a party my parents were giving and reciting Blake's Tyger, Tyger burning bright to the guests, complete with growling noises; I was four, and when I was done my mother swept me up and kissed me and everyone applauded. She was wearing dark lipstick and I insisted on going to bed with her lip prints on my cheek. I remember her sitting on a bench in Warren Park while my dad pushed me on a swing, and she bobbed close and far, close and far.

One of the best and most painful things about time traveling has been the opportunity to see my mother alive. I have even spoken to her a few times; little things like "Lousy weather today, isn't it?" I give her my seat on the El, follow her in the supermarket, watch her sing. I hang around outside the apartment my father still lives in, and watch the two of them, sometimes with my infant self, take walks, eat in restaurants, go to the movies. It's the '60s, and they are elegant, young, brilliant musicians with all the world before them. They are happy as larks, they shine with their luck, their joy. When we run across each other they wave; they think I am someone who lives in the neighborhood, someone who takes a lot of walks, someone who gets his hair cut oddly and seems to mysteriously ebb and flow in age. I once heard my father wonder if I was a cancer patient. It still amazes me that Dad has never realized that this man lurking around the early years of their marriage was his son.

Her Fearful Symmetry

Her Fearful Symmetry The Time Traveler's Wife

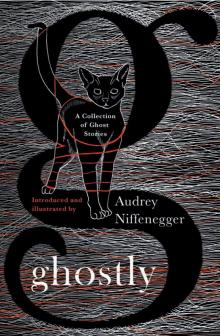

The Time Traveler's Wife Ghostly: Stories

Ghostly: Stories Magic

Magic Ghostly

Ghostly